How to get the most out of the

Who is Invisible Challenge

1

How to Get the Lesson

You can download the FREE slideshow and lesson plan here

Note: If you are using Microsoft Powerpoint, there are two issues you might have to deal with.

How much prep will you need?

NO PREP

If you’re comfortable teaching this kind of stuff:

Grab the slideshow file

and have fun!

SOME PREP

Go through the lesson plan and script for possible discussion ideas.

Check out the additional teaching tips.

PREP

Everything in the previous two options

+

Upgrade to the handouts and review the answer key to provide additional scaffolding for students

2

Fixing Microsoft Powerpoint issues

First of all, if you have any questions or need help, please email me: [email protected]

There are two problems that come up if you’re using Microsoft Powerpoint.

(These problems do not affect the Google Slides version.)

- PowerPoint Problem #1: I can’t edit the file

- PowerPoint Problem #2: The text and layout looks messed up

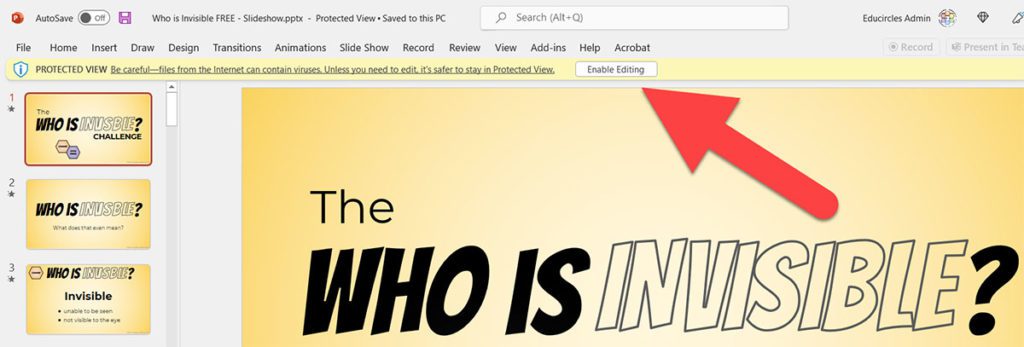

Microsoft Powerpoint Problem #1: I can’t edit the file.

This problem happens whenever you download a file from the internet.

Powerpoint opens up in Protected View because files from the Internet can contain viruses. (You should see a yellow warning bar at the top of the window.)

Solution:

- Just scan the file using whatever anti-virus software you have installed on your computer.

- Once you click the “Enable Editing” button, you’ll be able to edit the PowerPoint file and customize it for your classroom needs.

Microsoft Powerpoint Problem #2: The letters and layout is messed up

In some rare cases, when you open the slideshow, it will look messed up.

This problem happens because the fonts I used in the slideshow are not installed on your computer.

(To be honest, this shouldn’t happen at all. I embed the fonts into the slideshow file so PowerPoint should have the fonts… but, the internet is a weird place and unexpected things happen.)

Solution:

- You’re going to need to install the comic book font I used in the titles.

- You can get the font for free from the Google Font repository: Bangers font. (Click the “download family” button in the top right corner of the Google Font page.)

- After you install the font, don’t forget to shut down PowerPoint completely (or the fonts won’t load.)

For complete step-by-step instructions, please watch this video.

3

Teaching Ideas

Who is Invisible is one of my favourite lessons.

I like it because it guides students through the thinking process. You just have to facilitate and moderate the class conversation.

How we facilitate these conversations can influence whether the class discussions are incredibly powerful, thought-provoking, and empowering… or accidentally harmful, discouraging or excluding.

Every classroom is different!

You might want to check with your principal about this lesson before you teach the Who is Invisible challenge!

Here are a few things to consider!

Table of Contents

1. Think about “Intent vs Impact”

We may have the best intentions, but sometimes our actions may have a negative impact.

During my teaching career, I’ve been on both sides of the intent versus impact coin.

One time, I was teaching a lesson about stereotypes.

- I was trying to breakdown stereotypes.

- But, the examples I used accidentally reinforced negative cultural stereotypes and created a damaging environment.

- Although I had good intentions, my lack of cultural competencies made things worse for some students.

- I still feel bad about this. It’s shaped the way I teach.

One time, my Grade 8 students and I watched a play about bullying.

- The play was trying to explore the tragic consequences of bullying as a cautionary tale.

- But, the examples they used accidentally reinforced negative mental-health stereotypes and created a damaging environment.

- Although the school play had good intentions, their lack of mental health competencies made things worse for some people.

- I still feel bad about this. It’s shaped the way I teach.

Does this mean that we should avoid discussing racism, sexism, discrimination, and mental health challenges in the classroom?

I believe we need to have courageous conversations about racism, sexism, discrimination, mental health and social justice in the classroom.

These important conversations can be difficult because they can bring up powerful emotions and opinions, as well as political and controversial issues.

I think it’s important to try to keep a Growth Mindset as we have these courageous conversations in the classroom.

- We are going to get things wrong.

- We are going to make mistakes.

- If we learn from our mistakes, we’ll get better at having these courageous conversations…

- But, we’ll still continue to make new mistakes.

In fact, we will never be perfect at having courageous conversations.

And that’s okay, because not everything works for everyone, all of the time.

The fear of making mistakes keeps us from having these important and courageous conversations.

So, we avoid conversations about race, gender, or inequity.

But then, things don’t change.

This is an opportunity to empower our students with skills to think critically about be active citizens who speak up when they feel something is wrong.

Let’s look at some strategies to help us teach the Who is Invisible lesson…

2. Start from within

One good idea when facilitating classroom discussions around groups of people and how they might be portrayed in society and media is to start from within.

This means thinking about

- who we are (self-awareness,) and

- our relationship with others (social awareness.)

Reflecting on who we are can helps us identify different sides of our identity.

We can wonder how aspects of our identity, our lived experiences, and our personal knowledge might influence our view of the world.

Start from within goes for ourselves, as well as for our students.

(The slideshow explores aspects of identity, but for a in depth exploration of this issue, please check out this Thinking about Thinking Critical Thinking lesson.)

Practical Tips:

- Allow students to generate the examples discussed in the classroom as opposed to the teacher providing examples for the class to explore. (This was one of the big learning moments from my intent vs impact mistake I discussed earlier.)

- Remind students that when we talk, we’re speaking from our own personal experiences. Our views may not necessarily reflect the views of others.

- Model for students that it’s okay not to know the answer. It’s okay to wonder and ask questions from a place of curiosity. We can’t know everything about everything so we’re going to have biases in our knowledge. Actively seeking out different points of view is part of critical thinking.

- Pause after you ask a question to give students an opportunity to contribute. Count to five (or ten) silently in your head before choosing someone to share a response. If we choose people who raise their hands right away, we might not be creating space for other people to share their ideas.

- Consider doing THINK, PAIR, SHARE. Ask students to think about their answer for 30 seconds without raising their hands (THINK.) Then, share ideas with a partner for two minutes (PAIR.) Finally, ask the class if anyone has an idea they would like to share with the class (SHARE.)

3. Ground Rules for Classroom Discussions

The “Who is Invisible” slideshow goes over ground rules at the beginning, but it’s a good idea to come back to this slide – especially during class discussions.

- You are allowed to have an opinion. Other people are allowed to have their opinion. Your opinions might be different, and that’s okay!

- Treat people with respect.

- It’s okay to agree to disagree. It’s okay to change your perspective, but they can also stay the same.

- Give people space to speak for themselves.

Remind students that we’re still figuring out who we are:

- Some parts of our identity might be easier to hide than others! Some parts of our identity might change. We might not know everything about ourselves yet…

- Our identity is personal. Sometimes, we’re happy to share who we are with others. Other times, we might want to hide some aspects of our identity from some people…

- Some parts of our identity might be easier to hide than others! Some parts of our identity might change. We might not know everything about ourselves yet…

Allow students the right to pass (with no explanation.)

- Some students may not want to share their thoughts. They also may not want to write down their thoughts for the teacher or class.

- Students may not want to draw attention to themselves or talk about an issue.

Moderate conversations and feedback – make sure students are not pointing out other students.

- Allies and friends can help by providing opportunities for others to be seen and heard as opposed to speaking on their behalf. The slideshow lesson touches on this issue later on (slides 58 – 59.)

- Ask people to give general examples without naming specific students (in this class or other classes.) We don’t want to accidentally “out” anybody here.

- Don’t assume. Just because someone looks Asian doesn’t mean they self-identify as Asian or with Asian culture. It also doesn’t mean they speak an Asian language, although they might. They also do not speak on behalf of all Asian peoples and experiences. We can only share our own perspectives built from our own lived experiences, values, and knowledge. The slideshow goes into stereotypes and single stories later on (slides 45-49)

Respect that it’s okay for everyone to be at a different point on their journey to self awareness and social awareness.

Some students may have already spent a good amount of time discovering who they are at this stage of life. Other students may not be as self-aware.

(To be fair, this also applies to teachers and adults.)

Very self-aware students can identify their personal and social identities. These students may:

- Recognize and identify different aspects of their identity. They may also recognize they have strengths in some aspects of their identity, but not all.

- Name their emotions and identify how their emotions, feelings, values, and thoughts connect with their personal and social identities.

- Reflect on their lived experiences and identify some moments of power, prejudice, or bias. They may also link how their lived experiences connect with their personal / social identities.

- See strengths and assets in their personal, social, and cultural identities.

But remind students (and ourselves), that self awareness is an individual journey. We move at our own pace and we are at different points of self awareness. And, that’s okay. It is what it is.

3. The Bystander Effect: We encourage what we do not address

Forget about teaching for a moment. Let’s think about ourselves and our conversations with others: friends, family, strangers on the street, etc.

We have the opportunity to define the boundaries in how people communicate with us.

- What you tolerate, you encourage.

- Discourage behaviors you don’t want repeated.

Imagine someone makes a comment that is slightly off-colour, unacceptable or incredibly inappropriate.

There are lots of ways to respond.

How you respond provides feedback to the other person about how you received the message.

- You could yell and scream at the person and clearly outline what you accept. (Aggressive)

- You can choose to be direct and straightforward. Simply let the other person know where your boundaries are. (Assertive)

- You could be sarcastic and make a snide comment, hoping the other person picks up that the message was offensive. (Passive-Aggressive)

- You could do nothing. (Passive)

Doing nothing signals to the other person there was nothing wrong with what they said.

We’re essentially training that person that it’s okay to communicate to us in that manner. This is what the phrase, “what you tolerate, you encourage,” means.

Of course, we need to pick and choose our battles.

- Some battles are more important than others.

- Sometimes, we can do everything right and communicate assertively, and still “lose.”

Pause for a moment and think about how other people treat you. Are there any patterns in how you respond to comments?

(Please note: The Who is Invisible lesson does outline ground rules for communication. But, it does not go into the difference between assertive, aggressive, passive-aggressive, and passive communication styles. If you would like to help your students explore communication strategies and styles, please check out this Communication lesson.)

Discouraging behaviours doesn’t have to be done in an aggressive manner.

Here’s a personal example.

I am Asian and I live in Ottawa. Both of my parents immigrated to Canada from a country in Asia, but I was born and raised in Canada.

Sometimes, people ask me, “Where are you from?”

I’ll answer, “I’m from Canada.”

They’ll follow up with, “No, where are you really from?”

I’ll pause for a moment like I don’t understand. Then I’ll say, “Oh! I’m from Toronto.”

Why does this matter?

I’ve noticed that sometimes when I’m with a friend who is White, when they get asked where they are from, the other person accepts at face value that my friend is from Canada.

The assumption some people have is that people from Canada are White.

While there are lots of people from Canada who are White, there are also lots of people who are BIPOC. (Here’s more information about the term BIPOC being around everywhere now and how people may or may not identify with it.)

How we choose to deal with casual racism, inappropriate comments, or unfair things in life is an individual choice.

We control our actions and our attitudes.

By choosing not to speak out when we see something wrong, we are essentially giving permission for that behaviour to continue.

The “Who is Invisible” lesson is about giving students permission to be active citizens and think critically about society, media, and their place in it.

Citizenship doesn’t mean just holding a passport, living in a certain area, or belonging to a group of people.

- Active citizenship isn’t about everyone agreeing.

- It’s about helping your community: your class, your school, your local area or the country you live in.

- It’s about doing your part. That includes speaking up to defend your community, but also speaking up when you think what your community is doing something wrong. (It’s about helping to change the system from within.)

(If you’re looking for more resources to help explain civics and active citizenship to students, check out these 17 classroom debates.)

The Bystander Effect and Active Bystanders

The bystander effect is a documented psychological effect where people are less likely to act if there are other people around.

Basically, if you have a large group of people and someone does something offensive, people are less likely to step in and do something.

One idea is that the responsibility to act is spread out among everyone there. Nobody takes action, but everyone hopes inside that someone will say something.

Active bystanders are people who see something wrong and choose to respond. They take action to address the problem.

- This can be action during the conversation. (“Hey, that’s not cool when … “)

- This can be action later on after the conversation. (“Hey, it wasn’t cool when …”)

Being an active bystander doesn’t mean you have to be aggressive. We are confronting the issue in a style that works for us.

- You could make a funny or sarcastic comeback.

- You could be direct. Tell the person making the comment to stop. Check in with the person receiving the comment if they’re okay.

- If you see the conversation going towards a negative place, you could distract. Change the conversation or make a white-lie to get out of the situation.

- Not everyone likes to take action. You could also delegate someone else who likes this kind of stuff to step in and take action.

(Here’s a good read about How to Be an Active Bystander When You See Casual Racism.)

Teaching is tough. We have to pick and choose our battles

Teachers are not perfect.

We have to pick and choose our battles carefully. Investing time and energy in one area means less time and energy to do other things.

Teachers have a lot to do.

- We can suffer from imposter syndrome and feel like we’re never doing a good enough job.

- The burn out is real.

- The job is constantly changing. (Hello, Covid.)

- A first year teacher is expected to do the same quality job as a veteran teacher.

- The toll on our mental health can be significant.

Sometimes, we have to turn a blind eye to minor issues.

This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Remember, it’s okay to be assertive and protect our personal boundaries. Sometimes, we have to pick and choose our battles.

My school had a rule about no hats inside the building.

(I’m sure you have an instant opinion about that rule, but read on!)

We had a staff meeting facilitated by the principal and vice principal. The issue was debated, and then voted on.

Some teachers loved this rule; other teachers thought it was stupid. Some teachers were quite passionate about the hat rule and others couldn’t care less.

As you can imagine, different teachers enforce rules differently.

Some of us religiously enforced the hat rule because it was important to us.

Or, we religiously enforced the hat rule because we were team players. The hat rule was democratically agreed upon (by the teachers.) We might feel the rule is out-dated and a waste of energy, but we think it’s important to be a team.

Other teachers wore hats – not necessarily in protest, but because they wore hats in their regular lives and simply forgot to take the hat when coming inside the school.

And a few teachers wore hats.

I’m in the enforce rules camp because I think it’s important to be a team player… but sometimes, you have to pick and choose your battles.

What happens when we don’t enforce classroom rules consistently?

A few times, I’ve gotten to my classroom with only a few seconds to spare.

Say I’m rushing to class and I see a student wearing a hat in the hallway.

- If I know this student probably forgot and that with a little eye contact, nod, and gesture to take off the hat, the kid would likely take off the hat, I might choose to non-verbally signal to the kid to take off their hat.

- On the other hand, if I know from personal experience that this student wearing the hat sometimes responds in challenging ways and in the past, it took me 20 minutes to deescalate a situation, in that case I might choose to ignore the hat and rush to class.

- And of course, sometimes, I rush by a student wearing a hat because I genuinely didn’t even notice the hat.

What happens if you pass by a student wearing a hat, but you don’t enforce the rule?

- The student might not realize they were doing anything wrong.

- They might feel like the hat rule isn’t enforced so it’s okay to wear a hat inside.

- Students who choose to follow the hat rule might feel it’s unfair that some people get to wear a hat inside. Maybe they notice patterns in who gets away with wearing a hat, and who doesn’t.

- Other people might question why we even have this hat rule? Should taking off your hat inside the building even matter?

- Some people might feel that wearing a hat inside is disrespectful. So, if a student gets away with being disrespectful, it might make the school feel a little unsafe. The school is lawless.

This was for an arguably minor rule about wearing hats in school.

(My apologies if this is an important issue to you and I haven’t represented this issue well. We can chat more if you like – just email me at [email protected])

What happens if we’re having important courageous conversations in class about topics that matter, and we ignore inappropriate behaviour?

Creating a safe space means choosing to act when students make comments that are slightly off-colour, unacceptable or incredibly inappropriate.

The “Who is Invisible” slideshow goes over ground rules for classroom discussions.

But, it’s important to actually enforce the classroom rules, especially during important and courageous conversations about things that matter.

Here’s a golden rule for classroom management: We encourage what we ignore.

What happens if you pass by a student wearing a hat, but you don’t address casual racism, backhanded compliments, or incredibly inappropriate comments?

- The student might not realize they were doing anything wrong.

- They might feel like the ground rules for discussion aren’t enforced, so it’s okay to say anything, even if it’s disrespectful.

- Students who choose to follow the discussion rules might feel it’s unfair that some people get away with inappropriate comments. Maybe they notice patterns in who gets away with disrespectful comments, and who doesn’t.

- Other people might question why we even have these ground rules for discussion? Should there even be rules for conversation? Don’t we have freedom of speech to say whatever we want?

- Some people might feel that disrespectful comments are harmful. So, if a student gets away with being disrespectful, it might make the school feel a little unsafe. The school is lawless.

Students are watching us to see what is allowed and not allowed.

More importantly, we have the opportunity to model for students how to respond to difficult comments that we don’t necessarily agree with.

Why is it important that students learn strategies to respond to difficult comments (i.e. how to be an active bystander)?

(Note: The following information about violence against women is included on this page to help provide context about the importance of addressing sexist language. The Who is Invisible slideshow DOES NOT include any information about violence against women.)

Why do we need to call out sexist jokes, indifference or sexist comments?

Because “violence against women starts with words“

- Sexist jokes

- Indifference

- Sexist comments

- Disdain

- Blaiming

- Insults

- Yelling

- Humiliation

- Threats

- Sexual abuse

- Rape

- Physical abuse

- Murder

- Source: Inter-American Development Bank (“IDB”)

“No issue is too big or too small to intervene in. It’s the small micro-aggressions that perpetuate in society that left untackled allow these bigger issues to occur.”

Cambridge University: Breaking the Silence – How to be an active bystander. YouTube 2:14

Strategies to respond to inappropriate comments during classroom discussion.

Let’s look at some of the previous strategies to be an Active bystanders and see if we can apply them to the classroom.

Remember, not all strategies work for everyone all the time. But sometimes, it’s nice to think of options before you need them. Pick and adapt these classroom management strategies for your own style!

Active bystanders are people who see something wrong and choose to respond. They take action to address the problem.

Address the inappropriate comment during the conversation.

- This can be action during the conversation. (“Hey, let’s try to phrase things in … “)

- This can be action later on after the conversation. (“Hey, it wasn’t cool when …”)

Being an active bystander doesn’t mean you have to be aggressive. We are confronting the issue in a style that works for us.

- You could make a funny or sarcastic comeback.

- You could be direct. Tell the person making the comment to stop. Check in with the person receiving the comment if they’re okay.

- If you see the conversation going towards a negative place, you could distract. Change the conversation or make a white-lie to get out of the situation.

- Not everyone likes to take action. You could also delegate someone else who likes this kind of stuff to step in and take action.

4

Add-ons and Other Resources

that go well with this lesson

Here are some resources that go well with the FREE Who is Invisible Slideshow lesson.

Who is Invisible Paid Version

HANDOUTS + ANSWER KEY

Provide more structure to help scaffold student learning.

Upgrade to the PAID version of the Who is Invisible Lesson

The PAID version contains everything in the FREE version

- Slideshow (Google Slides,Microsoft PowerPoint)

- Lesson Plan (PDF)

And you also get handouts, an answer key, and an extended lesson plan.

- Handouts (PDF, Google Docs, Microsoft Word)

- Extended Lesson Plan (PDF)

- Answer / Discussion Guide (PDF)

The PAID version requires prep.

There are 40 files in total.

You get 43 pages of handouts and 35 pages of answers.

The extended lesson plan (66-pages) provides more scaffolding.

This helps provide step-by-step instructions for students to analyze and evaluate which groups of people are missing from the videos.

The PAID version has 13 lessons (13.5 hours of content / 810 minutes)

Lessons vary from 35 minutes to 105 minutes in length.

The lessons are based on topic as opposed to trying to have a standard classroom period in mind.

Everyone has a different period length anyway.

- Some teachers are using this in homeroom / advisory / guidance programs.

- Other teachers are using this in longer English Language Arts classes.